- Published on

Ion Propulsion, Generators, and 3D Printers

- Authors

- Name

- Cody Swain

- @c0dyswain

I loved hacking things together as a kid, and in college I thought that working on a startup was a way to extend that love to a career. I can now definitively say that this wasn't the case, for me. The passion I had for tinkering wasn't present in my startups, and I'd often feel depressed, exhausted, and strung out. There was this weight of feeling like I needed to continue working because the opportunity cost of leaving was too high. But the joy wasn't there.

There was a time when I built things, simply because I loved building things. This blog is motivated by a drive to rediscover that passion.

E-Recycling Arbitrage

The genesis of my interest in hacking things was legos - like millions of other kids. That evolved into electronics, and later software. My parents restricted the time I could spend on a screen, but gave me free reign to do nearly anything else. I ended up spending a lot of time buying broken electronics from the local e-recycling center. Mostly I'd just tear old printers apart -- building up a treasure trove of gear, belts, motors, and pcbs. Other times I'd be on the hunt for ways to make money.

There were two memorable instances where I made some quick cash: once I found a box of 50 adapters selling for $20 each on eBay. I paid $10 for the lot of them, and got a hefty payout. Another time I paid $10 for a "broken monitor." It was actually an iMac—which I knew but the disinterested employee at the recycling center didn't. I swapped in a new hard drive, and collected a reward of $600 from eBay.

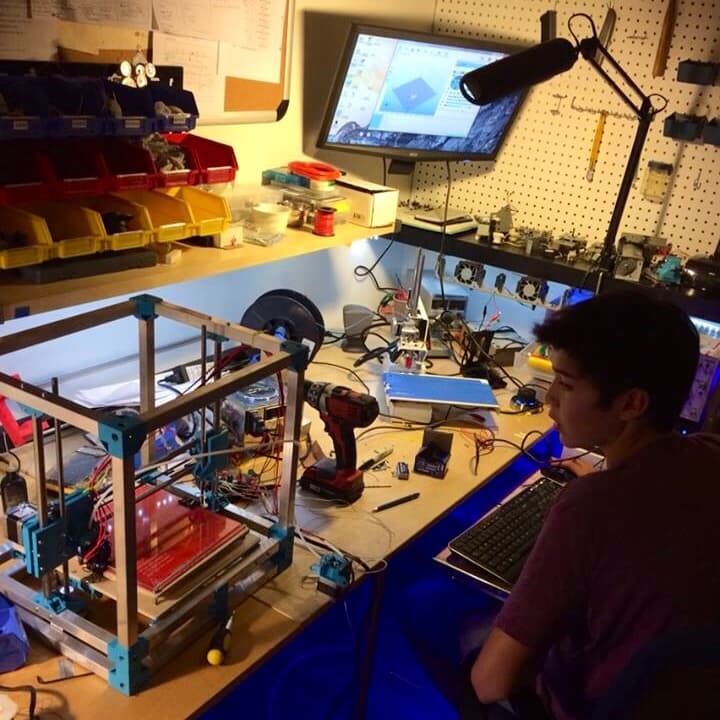

Like any growing enterprise, my profits went straight back into R&D. I bought a power supply, soldering kit, breadboard, oscilloscope, and plenty of other gadgets. I commandeered my parent's garage in 8th grade and set up my own tiny workshop, with peg-board walls, Arduinos, and eventually a 3D printer.

Self-Replication

3D printers would capture my attention for nearly all of high school. I remember assembling one from a wooden kit, and spending hours sitting there and watching it, as it extruded a tiny string of colored plastic filament. The most fascinating thing about the 3D printer was that is could improve itself. It could manufacture its own upgrades.

In a manner similar to bootstrapping a compiler, the printer could be used to create a more featured version of itself. I printed a new drive mechanism for the extruder, added a glass heated bed so the melted plastic filament would stick to the build plate, and constructed an enclosing case to prevent cold drafts from warping prints.

Eventually I learned that the printer could replace itself. I printed a new printer by cobbling together square aluminum tubing from Ace Hardware, a jumble of parts from McMaster-Carr, and set of printed components that I designed in SolidWorks.

The new printer was an improvement—its results were better. But the field of hobby 3D printing was evolving, rapidly. It was only a matter of time until the new printer needed to be replaced, and once again birthed the parts for its own replacement.

Kinetic Energy

I bet I could have spent hundreds of hours printing better and better 3D printers, but 3D printers always remained a means to an end for me. I was always seeking excitement, and naturally this led me towards fire.

First, there was the furnace for melting aluminum. It consisted of a metal bucket, with walls of heat-resistance concrete, and a fan blowing air into the bottom of the bucket via pipe. You could put aluminum cans into this bucket, and they'd melt in seconds. I intended to use this forge for creating molded aluminum components but the most I got was some entertainment.

Next came a hydrogen gas generator. I'd hook a car battery up to this device, and flammable gas would come out of a tube. Not only was it flammable, but violently explosive, producing the level of decibals that might motivate neighbors to open up the Nextdoor app.

The generator consisted of a bunch of stainless steel plates in parallel, encased in a plexiglass cylinder and capped with plastic endcaps at both ends. Stainless steel plates aren't easy to come by, but the local sheet metal shop was generous enough to donate some. There was also a bubbler—essential because it kept me from blowing myself up in the event that a stray flame ignited gas as it exited the generator. Inside the case was a mixture of water and potassium hydroxide — a flaky white powder. I'd hook a car battery up to the metal plates, and flammable gas would come out of a tube. The chemistry was simple enough, with a reaction occurring at the anode and another at the cathode.

The negative electrode produced hydrogen gas:

The positive electrode produced oxygen:

And you could collect oxygen or hydrogen gas at your choosing. But for my purposes, I wanted them both. Hydrogen gas burns, but a mixture of oxygen and hydrogen gas makes a bang. The product of this generator was the exact stoichiometric mixture required for complete combustion of hydrogen gas.

Which sounded like a 50 cal.